For the past couple weeks I have watched a web series titled The Artists Project. This series, put together by the Metropolitan Museum of Art is in its fourth season and continues to offer a fresh perspective on looking at art. Each of the short episodes features a contemporary artist looking at their favorite work in The Met’s collection. From masterworks by George Braque to objects made by unknown ancient craftsmen, the work discussed in the series covers the breadth of the vast collection, and the commentary provided by the artists brings a personal understanding of the work that often transcends the conventions of art criticism and history.

artistproject.metmuseum.org/4/jane-hammond/

One compelling look beyond what is traditionally considered art, is an examination of snapshots from the collection donated by Peter Cohen, by artist Jane Hamond. Hamond is examining images never intended as art, but she brings the expansive possibilities of Duchamp to contextualize the images into a sort of ready-made for her own work. The video encourages the viewer to see these snapshots in a new context, clean and clear on a matted background in high res, transforms the images from scraps in grandmothers drawer to mid-century masterpieces. She notes that one of the things that make these images so compelling is the total lack of professionalism and artistic intent, rather seeing the photos as a sort of taxidermy to collect moments of significance in the lives of those represented. It is then for us to use our powers of observation to appreciate the bold narrative and sometimes revolutionary composition.

Accompanying each of the videos is a short bio of the artist and an image of their work. If they, like Hamond, have a piece in The Met, a link is provided to the museum page of the work where the viewer can more fully consider the work being discussed on the artists own work. Its ready-made connection making that links the topics discussed in the video directly to the viewer, combining all in a conceptual whole.

One of the things I especially love about the series are the diverse voices represented. One such voice, is that of Paul Tazewell, an American costume designer for dance, theater and opera. Tazewell discusses the portraits of Anthony van Dyck.

artistproject.metmuseum.org/4/paul-tazewell/

Here Tazewell focuses on the precise rendering of the images, especially that of the clothing as the basis of his appreciation and inspiration. This rendering, notes the designer, supports a character and their narrative within the work. He notes the idealized and feminized garments express a different sort of masculine power than that of contemporary culture and sees affectation and character in the portraits themselves that feels very much like theater. He then offers a very frank appreciation of a self-portrait of the artist for its sensual qualities.

Through Tazewells eyes I see van Dyck’s work afresh. Rather that the stifling formality I have long associated with this type of painting, I can sense the vibrant world that the precision reflects and the designers joy in regarding the images is somewhat contagious.

Dia Batal is a Palestinian multidisciplinary artists who uses traditional text and formats in contemporary context. Her examination of a Syrian tile panel with a calligraphic inscription in another opportunity to see art outside of my own cultural context.

artistproject.metmuseum.org/4/dia-batal/

Originally born in Beirut and now living and working in London, she didn’t like seeing these objects removed from their homes and taken out of context in a museum. With the recent war in Syria however she has come to value their presence there so that they might be preserved.

The panel is not a work that would have attracted my attention without Batal’s introduction. I think this is likely because of its reliance on a message that I can not decode. Her reading the inscription aloud in the video opens the ear to the poetry contained in it in a way that a translation on a wall just couldn’t do. It opens the doors of a cultural context in a way that travel does, allowing a more intimate view of the words contained in the work.

The editing of the video is that of a slide show of portraits of the artist looking and photos of the art being considered, including closeups. As she discusses color composition on the piece, the closeup allows me to see the oxide cracking over the tin glaze of the tile and provides an entry for my appreciation of ceramic craft and history. This window gives me a genuine insight and appreciation for a work that before Batal’s discussion I found opaque.

Production is part of the reason this works so well. The slide show format combined with the voice over provided by the artist hold the cathedral-like space of the museum intact. As she imagines the tile in context of the mosque, imagining the dome and the light, we are given the open clean lines of the display, that echo the sacred intent of the space. This allows the viewer to contact the art in a fresh unhurried way that mimics actually being in front of the work.

One of the things I found most fascinating about the videos is to compare the work they make to the work they appreciate. My favorite example of this was Wilfredo Prieto’s discussion of the sculpture of Rodin.

artistproject.metmuseum.org/4/wilfredo-prieto/

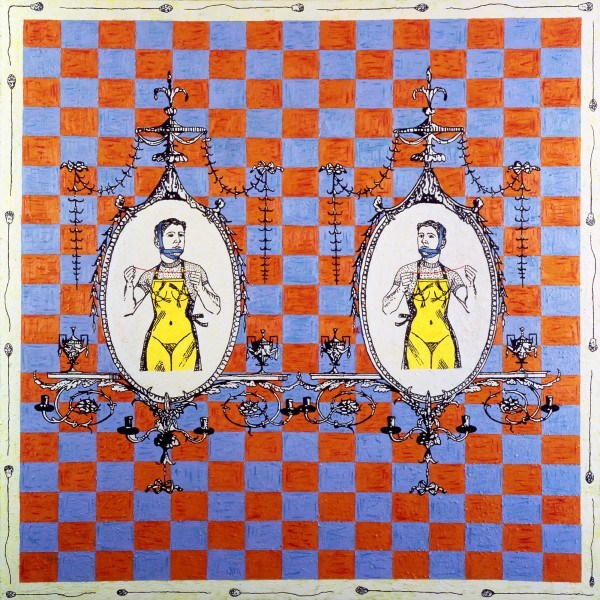

Prieto is a Cuban conceptual artist, and he uses his time in The Met to study. In the work of Rodin he finds inspiration in gesture. His careful examination of the studies on view share not only his understanding of the great artists technique but also the qualities he is looking for in his own work. He notes that Rodin believed to find expression in the material he had to dominate the material. Prieto takes this maxim into the conceptual realm with his work Yes No. Rather than dominating clay or plaster as Rodin did, he dominates objects, in this case fans, to replicate human gesture. His discussion of the masters work provides great insight into his intention with his own work. The static movement of Rodin’s figures informs the literal movement of the inferred figures in the fans.

https://vine.co/v/hmhhat3zYQh

I was not familiar with many of the artists in the series, one notable exception is Swoon. I’ve been a fan of her work for many years, yet I was initially surprised by her choice of art work to discuss. Swoon is a street artist working in some of the most non art venues in the world. Her choice of The Third Class Coach by Daumier struck me as inconsistent, being a heavily framed oil painting from over one hundred years ago.

artistproject.metmuseum.org/4/swoon/

In hearing the discussion however this choice becomes understandable. Swoon has looked closely at this work since she was 15. In it she finds its depiction of daily life speaking directly to her as she stands before the canvas, person to people and artist to artist.

Her discussion of the brush work in the face of the mother looking at her child really brings a painting I’ve seen many times into fresh focus, and her knowledge of Daumier’s biography and training gives insight into the choice of subject and motivation behind it.

It is in this motivation that we can clearly see this work as having a strong influence on Swoon. Both she and Daumier being passionate observers of cultural inequality and injustice. The two artists presentation seems so radically different when first considered, when taken in the context of the compassion that both artists base their view of the world on, the similarities become obvious, despite one hanging in one of the premier museums in the world and the other being wheat pasted to a wall in Brooklyn.